The current meltdown in Iraq has me revisiting the “Lessons Learned” topic I covered several months ago (see the post here). I’d like to address some of the readers’ comments from that post, and add some observations which have occurred to me since then. I will be discussing these thoughts in tandem with ideas from Isaiah Wilson’s article “The True Tragedy of American Power,” published in the Army War College’s Parameters, winter 2013-14 edition. (Read the article here.)

1. The American people should drive policy, and the military should execute it

John: “Let’s have the civilians, the voice of the people, make the policy and expect the generals to do their jobs, to develop strategy to attain those policies. But for that, we’ll need officers who can think (beyond managing their careers) rather searching through the database to find the right lesson to learn.”

Wilson’s message is, generally, that the American tendency over the last few decades to confuse force and power is our tragic flaw (which he artfully describes through literary metrics). He addresses the tug-of-war between civil and military solutions to foreign policy problems, explaining that the American military is extremely flexible and easy to deliver at the site of a problem, but it is terrible at resolving ‘dirty little wars.’

“The history of U.S. intervention reveals an inclination to using martial instruments to cure what are, essentially, political dilemmas.” (Wilson, 22)

Later, Wilson draws a parallel to ancient Rome. There, the act of imperial conquest itself had cascading effects which rotted the Republic’s original qualities.

“The mechanism that seems to lead a nation-state from liberal towards more imperial forms of intervention is military force itself, and particularly the manner in which it is used… Great care must be taken to ensure that the actions our own ‘legions’ take in defense of liberalism do not have the unintended effect of fostering illiberalism.” (Wilson, 23-24)

The key to this solution – that the American people drive their own foreign policy, rather than be dragged through hair-triggered military messes – is for the people to be engaged, and hold their representatives and executives accountable. And, on the military side of the coin, as John mentioned, high-level strategists and decision-makers can’t let themselves fall into the trap of the closed-loop, sterile, military-centric view of the world where they are hammers and every problem is a nail. One problem with the American public, is that they have become accustomed to equating force with power. That is, when there is a need for power to be exerted, the people turn to force for the solution.

2. The American social ideal is very liberal (in the traditional sense of the term), and perhaps not executable across all cultures

Steve brought up the point that it may be a bridge-too-far to provide an American-style democratic system in some societies.

Steve: “I’m surprised that Walt’s top ten didn’t mention trying to build an Islamic nation into our own image.”

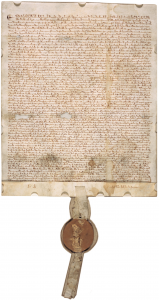

The Magna Carta of 1215, and its less-remembered, but equally important companion document, the 1217 Charter of the Forest, stand as the ground-breaking legal proceedings which led to the democratic republic we enjoy today. The process of forging government of/by/for the People took approximately six centuries for the Anglos (if you count the Magna Carta as the start point and the U.S. Constitution as the final expression of the idea – but it is still in progress, of course). I think it is idiocy to expect to produce the same result in non-European locales on a mere decades-long schedule. Before you too hastily accuse me of racism, keep in mind that I am primarily considering the mode of government – the structure that Englishmen finally threw off was feudal, and the structures in the Mideast and Southwest Asia are still tribal/feudal. I don’t personally know enough about the intricacies of Islamic law to say whether its religious aspects would prevent it from allowing some version of real democratic republicanism, but the fact that tribalism and feudalism persist in the Muslim world is enough to suggest that there is a long road ahead for the organic development of true government of/by/for the People.

So, back to the lessons-learned discussion: What should we learn from “trying to build an Islamic nation into our own image?” Wilson’s ideas about power and force are useful here also.

“Power, thus, varies with each and every relationship…it has to be developed and shaped… and will vary over time and place.” (Wilson, 19)

Our use and development of power in the Mideast cannot be the same as in Asia, or even Europe. And it certainly will be different now than it was in the 1960s. To reference my discussion of the Magna Carta, the differences between the social/political landscape of the U.S. and Iraq, for instance, must be considered. Looking for a lesson to learn can sometimes be useful, but the specificity of each situation makes the extrapolation and application of strategic lessons a dubious proposition. However perilous, Wilson puts his finger on one interesting commonality of our recent interventions:

“U.S. military interventions since 1989 have fostered tectonic changes in the international system.They have challenged traditional norms, principles, rules, and decision making procedures that have provided stability to the system for the past sixty years. In particular, U.S. interventions have challenged what was once considered largely inviolable – territorial sovereignty.” (Wilson, 20)

It’s as though we have taken the Monroe Doctrine and extended its reach to encompass the entire globe and relied preponderantly on brute force, rather than more subtle methods, to enforce it. Perhaps we should take a step back and consider the Golden Rule as it might apply to foreign affairs. How would we react if anyone else in the international community approached political problems with force in such an unbalanced way as we’ve done over the last two decades?

3. Magnanimity is an expression of power which does not always include force

Angus brought a savvy historical observation to the discussion in his comment on my original article:

Angus: “Too bad our President, Mr. Bremer and our State Department completely missed the lessons from rebuilding Germany, Italy and Japan, and failed to grasp the magnanimous, though not always perfect leadership of President Truman and Generals Eisenhower, Marshall and MacArthur.”

At the risk of referencing a lesson from a time and locale that could hardly be more different than Iraq circa 2003, i.e. post-World War II, the best thing to draw from this is: “Carrying a big stick” must be accompanied by the act of “walking softly.” When Bremer et al dismissed the Iraqi leaders carte blanche in the immediate aftermath of the 2003 invasion, the successful methods employed to rebuild Germany and Japan post-WWII (utilizing less-culpable indigenous civic leaders) were not followed, even though they may have worked.

Wilson hearkens beyond The Marshall Plan, and looks to the Monroe Doctrine as a fundamental version of American power.

“We should exorcise our goblins while welcoming the spiritual remnants of times when American power prevailed even in the absence of preponderant force.” (Wilson, 25)

In 1823, when the doctrine was expressed, the U.S. was nowhere near the status of “world power,” but was able to effectively cordon the entire Western Hemisphere. In addition to warning the European powers against further colonial efforts in the Americas, Monroe explained that the U.S. would also stay hands-off as the Central and South American nations built their own democracies. (This part has been conveniently forgotten at times, but should be remembered.)

“In short, what we see at the time of Monroe, and in the Doctrine itself, is a grand expression of American power at a time when American force was relatively anemic. This power-force paradox offers the United States great and important lessons for the gathering and learning as America’s capacities to generate and sustain force inevitably continue and decline while its global leader responsibilities increase and become more complex.” (Wilson 26)

Conclusion

Don made one of the insightful comments:

Don: “Keep in mind the difference between a lesson recorded and a lesson learned.”

The instructional value of any particular event is questionable, as we have seen, but it is even more tenuous if we merely identify or catalog the lesson, and stop short of correctly applying it in the future. I agree with Wilson, that now is the time for the U.S. to reassess what power looks like in the 21st century, and find ways to exert it without force (or with limited force). It is also time for a reassessment of what our global priorities are, and this must be at the approval of an educated American public.

Was this article interesting or useful to you? Please take a moment and share it with your friends on Facebook!

America’s citizens would require a massive engagement and education process to bring them up to even a baseline of being able to set policy, on top of dispelling national distrust of information. Increasing numbers do not perceive any justification for US international military involvement in any current conflict, not seeing beyond their noses at the implications. This is soluble; but how?

By reminding them of how they felt on 9/11. If we allow Al-Qaeda in Iraq, now the Islamic State, to maintain a foothold in Northern Syria and Northern/Western Iraq more attacks on western nations are guaranteed. We cannot allow a terrorist entity to form a nation state from which to operate unimpeded. The ugly reality no one speaks of is we, Western nations, were more secure by virtue of the dictators who had ruled over much of the Middle-East until the Arab spring. Having Assad in power is more advantageous to us than the alternative. Why hasn’t Israel been clamoring for Assad to step down? Because they realize the alternative to a dictator in the Middle-East is a broken state ruled by militias loyal to various Muslim sects. http://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Israeli-expert-on-Syria-The-West-and-Israel-are-not-in-hurry-to-get-rid-of-Assad-339456

Politically, I believe the best thing we could have done in Iraq is to have created a Sunni autonomous region equal to the Kurdish autonomous region, which is permitted by the Iraqi constitution. Additionally, we should have setup revenue sharing of the country’s vast oil wealth between the two autonomous regions and the central government in Baghdad. Iraqi Sunnis do not wish to live under the flag of the Islamic State, but they were being marginalized and imprisoned by the Shia led government after our withdrawal and saw little reason to resist the reemergence of Al Qaeda.